A Data Scientist’s Guide to Lazy Evaluation with Dask

We talk a lot about Dask and parallel computing, but sometimes we don’t do enough to explain the concepts that make it possible. Read on to learn how lazy evaluation works, how Dask uses it, and how it makes parallelization not only possible but easy!

What is Dask?

Dask is an open-source framework that enables parallelization of Python code. This can be applied to all kinds of Python use cases, not just machine learning. Dask is designed to work well on single-machine setups and on multi-machine clusters. You can use Dask with pandas, NumPy, scikit-learn, and other Python libraries.

Why Parallelize?

For machine learning, there are a couple of areas where Dask parallelization might be useful for making our work faster and better.

- Loading and handling large datasets (especially if they are too large to hold in memory)

- Running time or computation heavy tasks at the same time, quickly (for example, think of hyperparameter tuning or ensembled models)

Delaying Tasks

Parallel computing uses what’s called “lazy” evaluation. This means that your framework will queue up sets of transformations or calculations so that they are ready to run later, in parallel. This is a concept you’ll find in lots of frameworks for parallel computing, including Dask. Your framework won’t evaluate the requested computations until explicitly told to. This differs from “eager” evaluation functions, which compute instantly upon being called. Many very common and handy functions are ported to be native in Dask, which means they will be lazy (delayed computation) without you ever having to even ask.

However, sometimes you will have complicated custom code that is written in pandas, scikit-learn, or even base python, that isn’t natively available in Dask. Other times, you may just not have the time or energy to refactor your code into Dask, if edits are needed to take advantage of native Dask elements.

If this is the case, you can decorate your functions with

@dask.delayed, which will manually establish

that the function should be lazy, and not evaluate until you tell it.

You’d tell it with the processes .compute() or

.persist(), described in the next section.

Example 1

def exponent(x, y):

'''Define a basic function.'''

return x ** y

# Function returns result immediately when called

exponent(4, 5)

#> 1024

import dask@dask.delayed

def lazy_exponent(x, y):

'''Define a lazily evaluating function'''

return x ** y

# Function returns a delayed object, not computation

lazy_exponent(4, 5)

#> Delayed('lazy_exponent-05d8b489--554c-44e0--9a2c-7a52b7b3a00d')

# This will now return the computation

lazy_exponent(4,5).compute()

#> 1024

Example 2

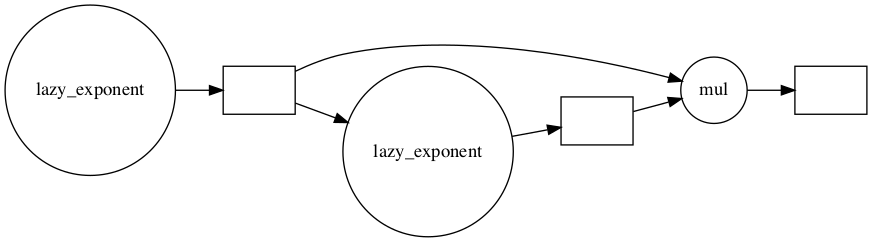

We can take this knowledge and expand it — because our lazy function returns an object, we can assign it and then chain it together in different ways later.

Here we return a delayed value from the first function and call it x. Then we pass x to the function a second time and call it y. Finally, we multiply x and y to produce z.

x = lazy_exponent(4, 5)

y = lazy_exponent(x, 2)

z = x * y

z

#> Delayed('mul-2257009fea1a612243c4b28012edddd1')

z.visualize(rankdir="LR")

z.compute()

#> 1073741824

Persist vs Compute

How should we instruct Dask to run the computations we have queued up

lazily? We have two choices: .persist() and

.compute().

Compute

If we use .compute(), we are asking Dask to

take all the computations and adjustments to the data that we have

queued up, and run them, and bring it all to the surface in Jupyter or

your local workspace.

That means if it was distributed we want to convert it into a local

object here and now. If it’s a Dask Dataframe, when we call

.compute(), we’re saying “Run the

transformations we’ve queued, and convert this into a pandas dataframe

immediately.” Be careful, though- if your dataset is extremely large,

this could mean you won’t have enough memory for this task to be

completed, and your kernel could crash!

Persist

If we use .persist(), we are asking Dask to

take all the computations and adjustments to the data that we have

queued up, and run them, but then the object is going to remain

distributed and will live on the cluster (a LocalCluster if you are on

one machine).

So when we do this with a Dask Dataframe, we are telling our cluster “Run the transformations we’ve queued, and leave this as a distributed Dask Dataframe.”

So, if you want to process all the delayed tasks you’ve applied to a Dask object, either of these methods will do it. The difference is where your object will live at the end.

Understanding this is really helpful to tell you when .persist()

might make sense. Consider a situation where you

load data and then use the data for a lot of complex tasks. If you use a

Dask Dataframe loaded from CSVs on disk, you may want to call

.persist() before you pass this data to other

tasks, because the other tasks will run the loading of data over and

over again every time they refer to it. If you use .persist() first,

then the loading step needs to be run only once.

Distributed Data Objects

There’s another area of work that we need to talk about, besides delaying individual functions – this is Dask data objects. These include the Dask bag (a parallel object-based on lists), the Dask array (a parallel object-based on NumPy arrays) and the Dask Dataframe (a parallel object-based on pandas Dataframes).

To show off what these objects can do, we’ll discuss the Dask Dataframe.

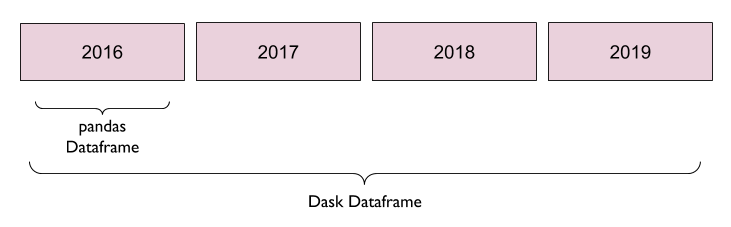

Imagine we have the same data for a number of years, and we’d like to load that all at once. We can do that easily with Dask, and the API is very much like the pandas API. A Dask Dataframe contains a number of pandas Dataframes, which are distributed across your cluster.

Example 3

import dask

import dask.dataframe as dd

df = dask.datasets.timeseries()

df

This dataset is one of the samples that come with your dask installation. Notice that when we look at it, we only get some of the information.

This is because our Dask dataframe is distributed across our cluster until we ask for it to be computed. But we can still queue up delayed computations! Let’s use our pandas knowledge to apply a filter, then group the data by a column and calculate the standard deviation of another column.

Notice that none of this code would be out of place in computations on a regular pandas Dataframe.

df2 = df[df.y > 0]

df3 = df2.groupby('name').x.std()

df3

#> Dask Series Structure:

#> npartitions=1

#> float64

#> ...

#> Name: x, dtype: float64

#> Dask Name: sqrt, 157 tasks

This returns us not a pandas series, but a Dask series. It has one partition here, so it’s not broken up across different workers. It’s pretty small, so this is ok for us.

What happens if we run .compute() on this?

computed_df = df3.compute()

type(computed_df)

#> pandas.core.series.Series*

That makes our result a pandas Series because it’s no longer a distributed object. What does the resulting content actually look like?

computed_df.head()

#> name

#> Alice 0.579278

#> Bob 0.578207

#> Charlie 0.577816

#> Dan 0.576983

#> Edith 0.575430

#> Name: x, dtype: float64

Example 4

Let’s return to the df object we used in the previous example. Here we

are going to use the npartitions property to

check how many parts our dataframe is split into.

import dask

import dask.dataframe as dd

df = dask.datasets.timeseries()

df.npartitions

So our Dask Dataframe has 30 partitions. So, if we run some computations on this dataframe, we still have an object that has a number of partitions attribute, and we can check it. We’ll filter it, then do some summary statistics with a groupby.

df2 = df[df.y > 0]

df3 = df2.groupby('name').x.std()

print(type(df3))

df3.npartitions

Now, we have reduced the object down to a Series, rather than a dataframe, so it changes the partition number.

We can repartition() the Series, if we want

to!

df4 = df3.repartition(npartitions=3)

df4.npartitions

What will happen if we use .persist() or

.compute() on these objects?

As we can see below, df4 is a Dask Series with

161 queued tasks and 3 partitions. We can run our two different

computation commands on the same object and see the different results.

df4

#> Dask Series Structure:

#> npartitions=3

#> float64

#> ...

#> ...

#> ...

#> Name: x, dtype: float64

#> Dask Name: repartition, 161 tasks

%%time

df4.persist()

#> CPU times: user 1.8 s, sys: 325 ms, total: 2.12 s

#> Wall time: 1.25 s

#> Dask Series Structure:

#> npartitions=3

#> float64

#> ...

#> ...

#> ...

#> Name: x, dtype: float64

#> Dask Name: repartition, 3 tasks

So, what changed when we ran .persist()?

Notice that we went from 161 tasks at the bottom of the screen, to just 3. That indicates that there’s one task for each partition.

Now, let’s try .compute().

%%time

df4.compute().head()

#> CPU times: user 1.8 s, sys: 262 ms, total: 2.06 s

#> Wall time: 1.2 s

#> name

#> Alice 0.576798

#> Bob 0.577411

#> Charlie 0.579065

#> Dan 0.577644

#> Edith 0.577243

#> Name: x, dtype: float64

We get back a pandas Series, not a Dask object at all.

Conclusion

With that, you have the basic concepts you need in order to use Dask!

- Your custom code can be made parallelizable with

@dask.delayed - Dask’s ecosystem has robust native support for pandas, numpy, and scikit-learn functionalities, giving them parallelization capability

- Dask data objects can make your data distributed, preventing struggles with too much data/too little memory

By combining these great features, you can produce powerful, production-quality data pipelines with the same APIs that we use for pandas, numpy, and scikit-learn. To see more about what Dask can do, come visit us at Saturn Cloud to read about our customers' successes with Dask!

Image credit: Manja Vitolic on Unsplash